Ole Viravong Scovill was just seven years old when she started drawing. First, it was a comic book; she created a story about a girl who wants to become a painter, but is too poor to realise her dream.

Later, growing up in Vientiane, she would buy magazines, and copy photographs of actors and singers. As soon as she finished school, she went to art school in Issan, Thailand. At just 18, it was the first time Ole had ever left her family, much less the country.

Later, growing up in Vientiane, she would buy magazines, and copy photographs of actors and singers. As soon as she finished school, she went to art school in Issan, Thailand. At just 18, it was the first time Ole had ever left her family, much less the country.

What followed was a rigorous, five-year journey of discovery, in which she discovered several things. The first was that studying art, and being an artist, was truly difficult. There were weeks, months and years of perfecting one subject – the nude body, hands, flowers, sunrise and sunset – before moving onto the next.

The second discovery was a complicated relationship with colour. One of her professors warned her she might be colour-blind, as her works tended to be dark – physically and thematically. For her final thesis, she chose prostitution as her theme, and spent six months researching her subject on the streets of Bangkok, and also back in Vientiane.

“My professor had suggested with the prostitution theme to try dark colours,” she says. “I did purple and blue, and I even tried red, a sad, hot colour. But they still came out brown.”

“My professor had suggested with the prostitution theme to try dark colours,” she says. “I did purple and blue, and I even tried red, a sad, hot colour. But they still came out brown.”

She graduated in 2000 and returned to Vientiane to live with her father and sister, bringing some acrylics and paper with her. She says it was when she met her future husband, an American translator who also liked to draw, that her sense of colour finally returned.

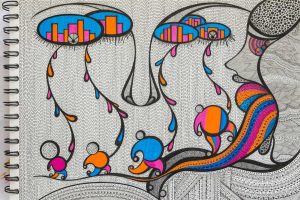

Since then, and especially since moving to the United States, colour, joyful and rampant, has been a mainstay throughout her works, and she often spends days at a time mixing the right shades before starting a new painting.

T he third revelation to arrive during her art school days was that the stubborn streak she had always shown as a child was growing, as she became an adult, into fully fledged feminism.

he third revelation to arrive during her art school days was that the stubborn streak she had always shown as a child was growing, as she became an adult, into fully fledged feminism.

Two decades on, and her works – mainly painting, but also photography and installation – still focus continuously on the female form. Sometimes these forms are vivid, meticulously detailed, fantastical and disembodied, and often confronting.

She often describes her subject matter as “aggressive”, a word that has as much to do with the reaction she often gets as her own thought processes. Back in Laos after nine years in California, she is grappling with the reactions she gets from locals, be they government officials concerned at her nude depictions, or timid art students, awed by the possibilities of the world she has opened up for them.

Meanwhile, there is another female artist hunkering down in her Vientiane workspace, also struggling to find her voice and make it heard.

Back when Ole was already a teenager, this other girl, Souphaluck Phongsavath, was also discovering her love of drawing, and a way of protecting herself against the spirits she had always been so scared of as a child.

Souphaluck remembers growing up in Xayaboury province, when she would hurry past the temple on way home, afraid of what might be in there, waiting. But that changed when, one day, her mother pointed out the paintings inside.

Souphaluck remembers growing up in Xayaboury province, when she would hurry past the temple on way home, afraid of what might be in there, waiting. But that changed when, one day, her mother pointed out the paintings inside.

“When I first saw paintings on the wall and inside the temple, it was amazing,” she says. “They were images of Buddhas – items I saw every day but in a different dimension – and I just thought, wow.”

Her fear of temples was gone, replaced by a love of drawing that has never gone away. Watching her copying out the images she saw, her aunt realized the family had an artist on their hands, and eventually encouraged her to study art in Savannakhet as a high school student.

Souphaluck went onto the study at the National Institue of Fine Arts in Vientiane – nine years of art study in all. But she found most of her learning happened in the library of the capital’s Institute Francaise, with its library well-stocked with art books. It was there that she discovered the works of European artists like Van Gogh, and understood, truly, how many different ways there were of looking at the world.

Souphaluck went onto the study at the National Institue of Fine Arts in Vientiane – nine years of art study in all. But she found most of her learning happened in the library of the capital’s Institute Francaise, with its library well-stocked with art books. It was there that she discovered the works of European artists like Van Gogh, and understood, truly, how many different ways there were of looking at the world.

She says she learned more from looking at the works of others – fellow students, or travelling exhibitions from neighbouring countries – than she did at university. Her experience at art school in Vientiane was markedly different to Ole’s. For starters, she arrived too late to secure a spot in the painting class, and had to settle for wood-cutting instead.

But despite her disappointment at the time, today her work is still informed by her earliest learned techniques; the woodcuts create the textures she uses most often in her paintings.

Hearing her talk about her work, one might be forgiven for thinking it is a refined version of the religious and traditional depictions commonly seen in temples.

“I love flowers, I love the lotus, and I use Lao patterns and motifs in my work,” she says.

But up close, the works are startlingly original and daring. Large-scale and intricate, her paintings do, indeed, feature lotuses and traditional female forms from Buddhist teachings. But these motifs are often entwined around a naked female body, or an otherworldly figure, faceless and discomfiting, dreamlike, drifting through schools of silver fish.

And while there are connections throughout her work – she has been practicing full-time since she left university – she makes a point of forgetting each work as soon as she begins the next.

“The art looks like it’s connecting, but something is always different and I’m always learning,” she says. “This shows through each new painting.”

She has no intention of undertaking any more formal study, and prefers to learn from life, and the people around her.

“Artists can understand when they look at your work,” she says. “We all speak one language, even if we’re not talking. We know when we show work we’re exchanging ideas. I love to study like that, not in university.”

Despite their age difference – Ole is 41, Souphaluck 31 – and distinct artistic journeys, the two women have much in common as they work to maintain a practice in what is something of an artistic back-wood. Both are raising sons, and both rely on the help and understanding of their families to enable them to truly immerse themselves in their practice.

It’s a rare sight, not least in Vientiane, where even male artists are restricted by physical resources and teaching methods. Ole is sometimes distraught, but more often optimistic, to think of the nascent artistic talent lies dormant throughout the country, and tries hard to make herself available as a mentor to artists like Souphaluck.

Written by: Sally Pryor

Photos: Phoonsab Thepvongsa

Originally Published in: Champa Meuanglao, 2018 January-February Edition