It was 80 years ago, and the morning of 6 August 1945, when the sky above Hiroshima turned white.

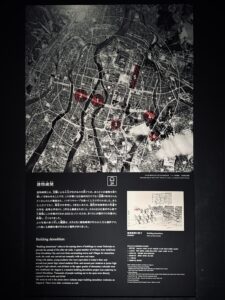

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima was carried out by the United States during World War II to force Japan’s surrender, marking the first use of nuclear weapons in warfare and killing over 100,000 people instantly or within days.

“I Thought the Sun Had Fallen”

“It was brighter than anything I had ever seen,” said Kuwamoto Katsuko. “I thought the sun had fallen.”

Born in 1939 and only six years old at the time of the atomic bomb, Kuwamoto was a young schoolgirl attending class in Hiroshima, just 3.5 kilometers from the bomb’s hypocenter.

The bell had just rung to signal the start of class when a sudden explosion shattered the school’s windows with a deafening roar.

Outside, entire buildings lay in ruins, smoke choked the sky, and flames consumed the streets. Kuwamoto’s home, which was located closer to the city center, had collapsed under the blast.

“After the blast, my mother was trapped under the debris of our wooden house,” Kuwamoto recalled. “A neighbor heard her voice and dug her out. Together, they ran away from the fire, crossing Mount Hijiyama to reach safety.”

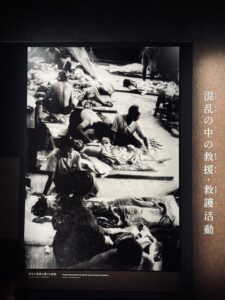

Three days later, when the fire finally died down, Kuwamoto, her aunt, and her sister set out to look for her. What they found instead were burned bodies covering the streets, their features unrecognizable, swollen by burns and heat.

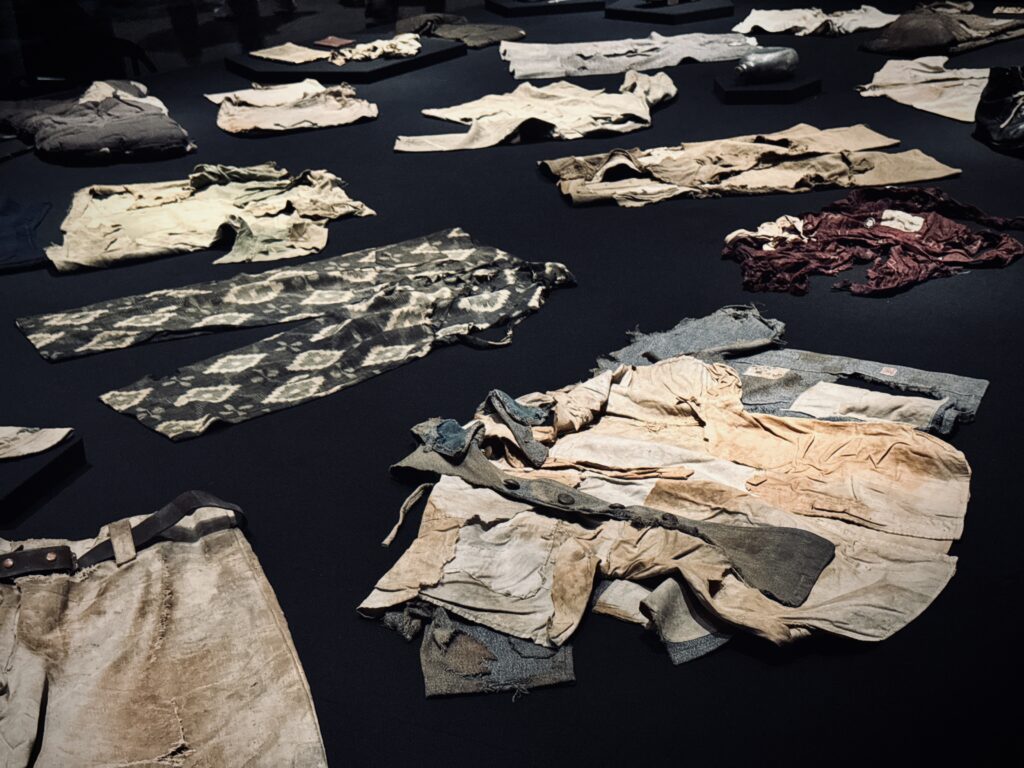

“There were no clothes left on them. We couldn’t tell if they were men or women. Everyone looked the same, melted, disfigured.”

The Silent Death of Radiation

When Kuwamoto’s mother eventually found her way to them, she appeared fine at first glance, but something was wrong.

“She looked okay, but her skin had turned pale like I’d never seen before,” Kuwamoto said. “Later, we learned that the radiation had destroyed her ability to produce blood. There was no visible injury, but death was already inside her.”

In the weeks that followed, her mother’s health declined. Despite the war’s end, there was no relief. Food was scarce, and she bartered her precious kimonos in exchange for rice and vegetables.

Stories in Artifacts

For 80 years, it has lived on in memory, in silence, and in the stories of survivors like Kuwamoto Katsuko.

The memory of Hiroshima lives on, not only in the words of survivors like Kuwamoto but also in the small, haunting artifacts left behind, carefully preserved in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

A Tricycle Buried with a Boy

One exhibit displays a rusted tricycle and a dented metal helmet. They belonged to Shinichi Tetsutani, a boy just three years and eleven months old.

He had been riding the tricycle in front of his home when the bomb exploded. Severely burned, he died that evening, whispering for water. His father, unable to part with his son’s favorite toy, buried Shinichi with the tricycle in their backyard.

Forty years later, when the family transferred Shinichi’s remains to the family grave, they found his skull still resting inside the helmet.

The Lunch That Was Never Eaten

Nearby, another display features a charred lunch box and water bottle. They belonged to 13-year-old Shigeru Orimen, a junior high school student killed while helping with demolition work near the blast’s center. His mother later found the lunch box beneath his skeletal remains.

The meal inside, barley rice, soybeans, and shredded potatoes, remained untouched. Shigeru never got to eat the lunch he had looked forward to that morning.

The Silent Voices of Children

These items are not relics of war, they are the voices of children, forever silenced but still speaking through their belongings.

A Dome That Stands as Warning

Just outside the museum stands the Atomic Bomb Dome. Once the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the structure was one of the few buildings to survive the blast. Its scorched concrete walls and skeletal dome remain as a permanent memorial. A symbol of loss. A symbol of warning.

“When I see the Dome, I remember everything,” said Kuwamoto, who still lives in Hiroshima today. “But I also remember how lucky I was to survive.”

She shares her story not for pity, but to teach. “We didn’t know the word ‘atomic bomb.’ We didn’t understand what was happening. But now, the world knows,” she said. “So we have no excuse to forget, and no right to repeat it.”