Kai Sy remembers her childhood fondly, riding a water buffalo through the rice paddies and singing in Lao.

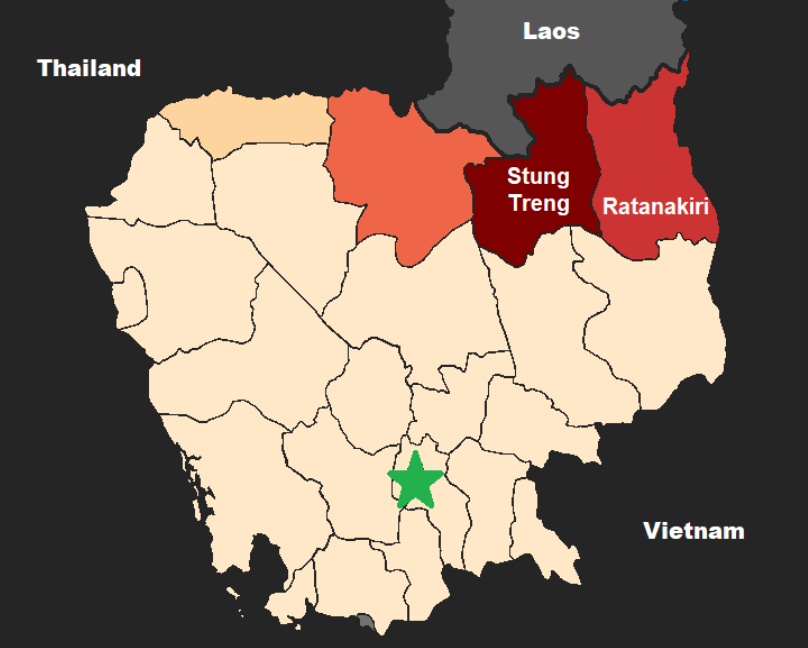

Though her home province of Ratanakiri has been part of Cambodia since 1904, Kai Sy grew up unable to read or write Khmer, preferring to speak Lao like most of those around her.

Today, she is a government functionary and fully literate in Khmer, yet still nurtures her Lao roots. Kai Sy performs traditional Lao songs to audiences across Cambodia, reaching those who speak Lao natively, but feel disconnected from their roots.

Despite being a significant part of Cambodia’s population, the Lao community lacks official recognition, placing them in a unique position within Cambodian society.

Nobody knows exactly how many Khmer-Lao (Or Lao Cambodians) like Kai Sy there are today, as they are not counted separately by the Cambodian census, because they are not registered as an “indigenous group” by the Cambodian government.

However, estimates fall between 50,000 and 100,000 thousand. If they were to be recognized as an indigenous group, they would likely surpass the Kuoy and Bunong, currently listed as the largest indigenous populations by the Cambodian Indigenous People’s Organization, with estimated populations of 70,000 and 50,000, respectively.

Cultural Roots and Identity of the Khmer-Lao Community

The Khmer-Lao community has diverged over time from mainland Laos, developing its own unique dialects. Many Khmer-Lao distinguish their way of speaking by referring to it as “Lieu,” as opposed to the “Lao” spoken in Laos.

“The Lao in Cambodia and the Lao in Laos have a lot of differences,” said Meach Mean, a Khmer-Lao government official. “Even the language cannot be understood by each other anymore.”

He went on to say the Khmer-Lao traditions today are 30-40 percent Lao in origin, with the rest being Khmer.

In 2001, the Cambodian government passed an amendment to the Land Law, giving specific protection of land rights for indigenous communities, and giving the first official recognition of indigenous groups as separate legal entities. However, the Khmer-Lao community was not included in this designation. As a result, they do not benefit from the same land protections afforded to the recognized indigenous groups nearby, leaving them vulnerable in terms of land rights and access to resources.

In 2015, local protests erupted over the construction of the Sesan Hydroelectric Dam, drawing attention from international groups and media, especially regarding the displacement of nearby Bunong villages.

Media reports showed that the much larger Lao community in the area received comparatively little recognition.

Today, the villages near the dam still mostly speak Lao, but there are no organized cultural groups to advocate for their rights and heritage. Many villagers flatly denied the existence of Lao culture, insisting that they were not a separate ethnic group from the Khmer, but rather spoke Lao due to their proximity to the border. They believed that, over time, even this connection would fade.

“The teachers decided that we should all speak Khmer, so we speak Khmer. Our children will learn only Khmer,” said a barber in Phlouk village, which is notable for having its own dialect referred to by other Khmer-Lao as “Original Lieu.”

He also mentioned that the children would not learn the dialect, a decision supported by the entire village. While outside sources claimed that many in Phlouk village were unhappy about the fading of their Lao heritage, no villagers felt comfortable expressing that sentiment in on-the-record interviews.

“They’re afraid that their loyalty to Cambodia is going to be questioned,” said Ian Baird, a professor of Southeast Asian studies at the University of Wisconsin, who specializes in indigeneity in Southeast Asia and Lao history, theorizing about the villagers’ reluctance to tell more about their culture.

Bainua, a 69-year-old resident, said that there was “no such thing” as Khmer-Lao traditions beyond language, as they are fully Khmer. He noted that his grandchildren would not learn Lieu, viewing this as beneficial for easier communication.

“One Khmer, two mouths,” Bainua and his fellow villagers repeated.

Another villager nearby explained that the local population identifies as Khmers, attributing the use of the Lao language to the fact that many had fled to Laos for a few years during the Cambodian Civil War in the 1970s.

Bits of History of Lao Immigration to Cambodia

After the decline of the Khmer Empire (1431 CE), Northeastern Cambodia received waves of immigration by Lao peoples who largely governed themselves, due to a lack of centralized authority by the Khmer state. Later, Lao Kingdoms such as Lan Xang and the Thai vassal Champassak took control of these areas, building urban centers such as the now regional capital of Stung Treng (A Khmerization of the original Lao name of Xiang Taeng).

When the French took over, they referred to these parts of Indochina as “Southern Laos,” before eventually transferring these territories to their Cambodian protectorate in 1904.

Today, there is a large population of ethnic Lao in these areas, in some localities even as a majority. In Cambodian’s Steung Treng Province and parts of Ratanakiri, many members of other minority groups, such as the Brao and Tampuan, also use the Lao language as a Lingua Franca.

According to Baird, some individuals identified as “Khmer-Lao” may actually be genetically unrelated to the original Lao populations, as they might come from other non-Khmer ethnic groups that have assimilated into the Lao community due to their widespread presence. He also believes that it would be more accurate to call the Khmer-Lao “Lao Cambodians,” as they are citizens of Cambodia but not ethnically Khmer.

“I am ethnically Lao, but Khmer by citizenship,” said Kai Sy, the Khmer-Lao singer, echoing Baird’s sentiment.

Baird has been working with the Khmer-Lao since 1995, and written extensively about their history and relationship with the government.

“It is probably one of the more oppressed groups,” he said over a call, comparing the Lao to other minorities that faced harsh policies.

He explained that in the 1960’s, there were fines for speaking Lao in the city of Stung Treng. Buddhist temples, which once served as centers of Lao culture and literacy, had their lay clergy replaced with Khmers.

In the following years, the Khmer Rouge, while brutal towards many ethnic minorities, took a lighter approach with the Khmer-Lao and other groups in the Northeast, initially leveraging their stronghold by using Lao in communications to evade the Cambodian government.

Today’s Stance and Community Sentiments

Today, the Cambodian government is more inclusive toward indigenous groups and minorities. However, opposition figures still sometimes use xenophobic rhetoric. This, combined with past experiences, can make Khmer-Lao individuals hesitant to discuss their heritage with outsiders, according to Baird.

Lieu Chovannari, a Khmer woman who married into a Khmer-Lao family, acknowledged the existence of cultural differences between Khmer and Khmer-Lao. She moved to the village ten years ago.

“When I first came here, there was some discrimination,” she said. “The elders would talk about me as an outsider.”

She added that it was difficult to adjust to “all their superstitions.”

However, not all Khmer-Lao have the same perspective on their cultural heritage.

“There are so many of us, but we have lost our way,” said Sai Bunlam, who has been working on creating an association for Khmer-Lao. “When it comes to ceremonies, weddings, house warmings, etc – there’s nobody who really knows it well and to keep our traditions alive. After the elders are gone, nobody will know or understand it.”

He hopes a formal Khmer-Lao organization will help lobby for Lao language education to preserve their culture. Although he received strong community support, momentum waned during the COVID pandemic, and economic challenges have hindered fundraising.

He envisions establishing Lao language and cultural centers, acknowledging that while full schools may be unrealistic, lessons could be offered in temples and community spaces.

“We want to preserve our identity for the next generation to know the way of life, traditions, and culture of their ancestors,” he said. “If we don’t do it, it will be lost.”

The Khmer-Lao community possesses a distinct culture that is vital to Cambodia’s cultural diversity. With support from the government and civil society organizations, efforts to preserve and promote Khmer-Lao traditions can continue.