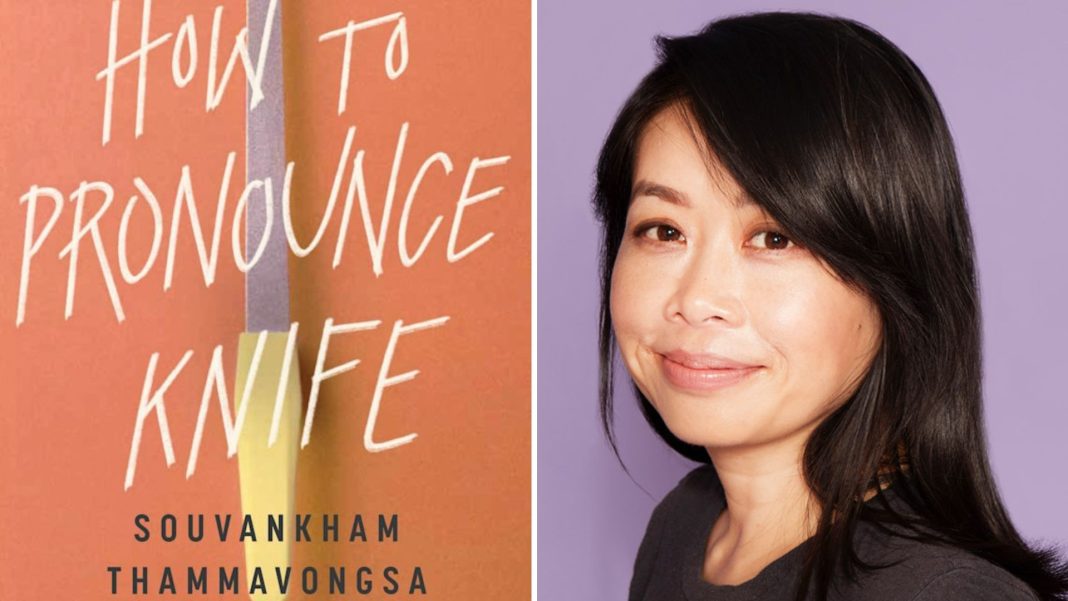

Born in a Lao refugee camp in Nong Khai, Thailand, award-winning Lao-Canadian author Souvankham Thammavongsa spoke to the Laotian Times about returning to the country of her birth for the first time and her much-lauded collection of short stories which chronicles the heartache and the wonder of the immigrant experience.

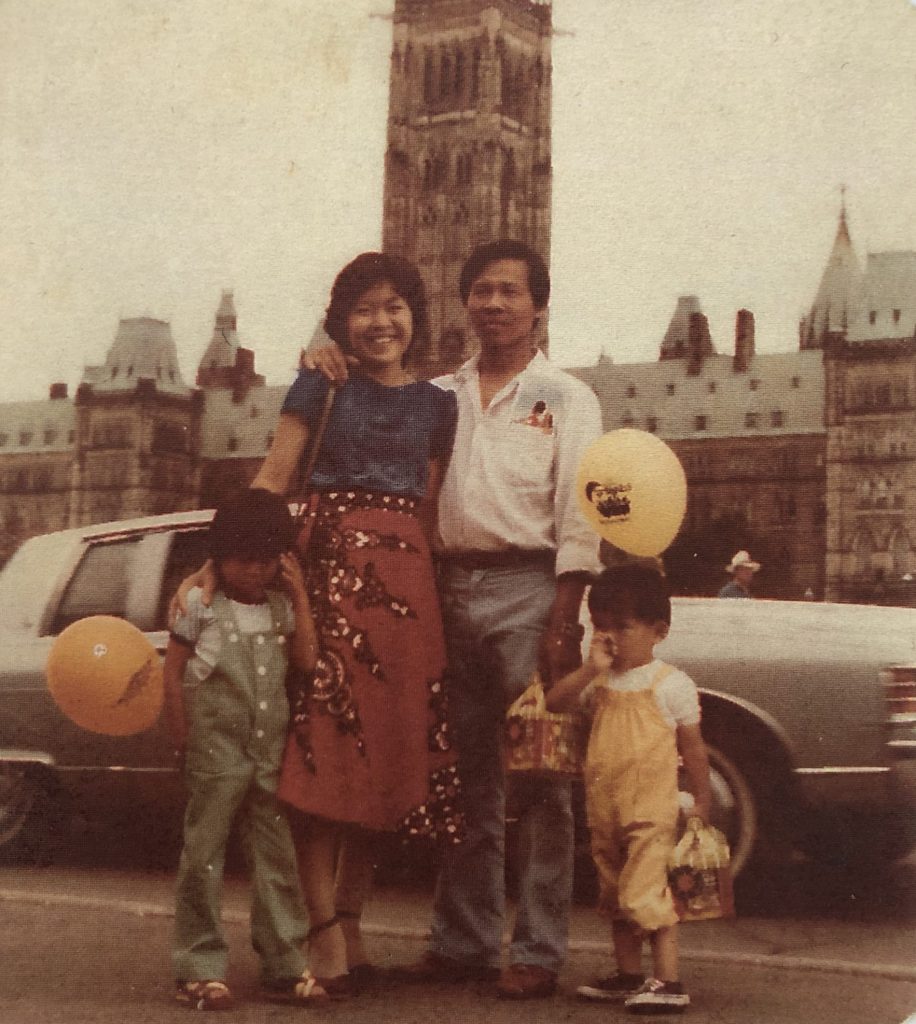

Researching a person before an interview is often akin to solving a puzzle. In the case of my new subject, a prolific and critically acclaimed author, I found myself reading her latest book cover-to-cover, going through her recent interviews, and listening to her slow, soft, and eloquent voice on various podcasts and interviews. I discovered that although she was born in a Lao refugee camp in Nong Khai in the late 1970s, she has not been back to Thailand since her family immigrated to Canada when she was a child. And, she has never visited Laos, the land of her ancestors, whose language, food, culture, and people she often writes about in her prose and poetry.

Souvankham Thammavongsa had said earlier that she was not emotionally ready to visit Thailand or Laos. She also spoke about how her extraordinarily hardworking immigrant family put her through college, especially her younger brother who worked long hours at their parents’ printing shop since he was in high school so that she could pursue a creative life. He was a strong pillar of strength, who bought numerous copies of her collection of short stories How to Pronounce Knife, after it won the most prestigious literary prize in Canada, The Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2020, for his friends to read and admire.

But just when I thought I was starting to make sense of Souvankham’s life story and how it inspired her work, I read her brutally moving essay in the New Yorker, which was published earlier this year about her growing up years and her brother’s sudden, tragic death. It made sense why she stayed away from the land of her birth for almost the entirety of her life, it made sense why she was visiting now.

She says, “There were so many things we never got to do that we always talked about doing. He was so proud to come from Laos, and he spoke Lao fluently. I want to take this trip for him and with my mother.”

The Lao-Canadian author will also be speaking at the Neilson Hays Bangkok Literature Festival 2023, which will be held from 4-5 November. At the festival, she’ll present a witty and thoughtful meditation on what it means to be a writer and will be in conversation with Pariyapa Amornwanichsarn, writer, translator, and Cultural Officer at the International Relations Bureau at the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Culture.

Although she has participated in literary festivals in Southeast Asia in the past, they were on Zoom. This is the first one she gets to attend in person.

She says, “I am looking forward to all of it—meeting other writers, hearing their talks and panels, sharing a meal, walking around, feeling the warmth of the weather, looking at flowers and plant life. And looking at my mother’s face as I get to do all this.”

In her writing, Souvankham wanted to challenge the assumption that immigrants and refugees are quiet and sad people who are ashamed of who they are, where they come from, the food they eat, and the language they speak. After all, she came from a family that is loud and has an amazing sense of humor, one that is proud of its food and language.

She says, “It’s often assumed that I am translated and that I write “in my own language.” Or I write about people arriving on boats, that my characters are sad and quiet lumps. I come up against a lot of expectations of what my themes and characters and stories should be, and I often have to work to undo these things which take me away from my writing and it makes me sound like I am telling only one story. I enjoy kicking at these assumptions and expectations. I knew what my writing and voice was going to be and do, very early on and I’ve kept to that.”

Souvankham’s short story collection highlights the life of ordinary people working in nail salons, meat processing factories, and school bus drivers, she writes about homemakers, older women, and children and injects their narratives with dreams, dignity, and desire. Her book is set in a nameless world that is only brought to life by the experiences of immigrants who live there.

“I didn’t want there to be distance between the characters and readers. A reader feels as nameless and displaced as a character in the story. No one is given their bearings,” she adds.

Although not a formally trained writer, but one who expertly juggles fiction and poetry, Souvankham feels that if people can read, they can teach themselves anything. She is aware that many aspiring writers think that they have to go to school and get formally trained to be one and that there are many schools that are happy to make a profit off of that and yet their students with their fancy degrees are still not writers.

She says, “It is very hard to become a writer. But the wonderful thing about being a writer is that you can come from nowhere and have nothing, and try to be one. I don’t like to give advice to writers, especially aspiring writers. They already know what they are doing.”

As we are currently living in a world ravaged by war, destruction, and loss of innumerable lives, like Souvankham’s parents in the 1970s, numerous families and individuals across the world have no choice now but to leave the place they call home, in search of safety and a semblance of security in a foreign land. I asked Souvankham if she thinks that publishing and other creative industries, which haven’t been quite inclusive in the past, have a responsibility to highlight these stories and experiences.

Souvankham says she has observed that publishing likes to fixate on one story or one writer and the same writer is brought out time and again to tell the same story, “It is fine for that one writer and I am thrilled for their work, but there is more than one. More than one story, more than one writer, more.

“It took me a long time for my work to reach a larger audience because as a refugee, I was not “sad enough”. My sense of humor didn’t register. My pride was confusing and even seen as a surprise. When I write fiction, I am often expected to lean on the truth or real-life biographical experience rather than the act of my imagination which my work holds most high. There are many experiences of being a refugee and all of them matter.”

Speaking of platforming diverse voices and stories, Souvankham recommends Chetna Maroo’s novel Western Lane which she recently read and loved, and hopes to see in the hands of many more people.

“I love the clarity of the language and how the words in her sentences force you to move slow. We often don’t see or admire the rigor and power in language when it is made to be so bare. We like noise and buzz and pop. And to insist on that quiet and bareness is courage and power. She does this in 140 pages. I love a writer confident enough not to do too much,” she adds.

Coming back to her own book, after How to Pronounce Knife was published three years ago, readers from across the world reached out to Souvankham about how her stories resonated with them. With new readers discovering and engaging with her work and her latest book at the festival this weekend, what does she want them to take away from it?

“That language is funny, tricky, powerful, disappointing, and beautiful. It doesn’t matter what language it is,” she concludes.