The ongoing design-related dispute involving Italian-based fashion house Max Mara, Laos’ ethnic Oma people Luang Prabang’s Traditional Arts & Ethnology Centre over the alleged unauthorized use of traditional ethnic textile motifs from the remote ethnic community in the firm’s fashion offerings is heating up with an online petition reaching 5,000 signatures.

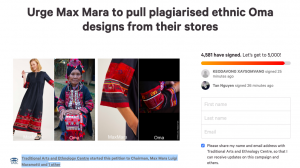

The petition entitled “Urge Max Mara to pull plagiarised ethnic Oma designs from their stores” was posted on the popular site change.org

The Laotian Times reported on the dispute earlier this month in the article “Max Mara vs Laos’ Oma Ethnic Group: Fashion Chain Facing Claims of Textile Plagiarism, Design Theft“.

Now, an online petition via Change.org to the owner of the Fashion Chain Max Mara was approaching 5,000 signatures as of 10 am Monday April 22 in Laos (UTC+7).

Max Mara has gone silent. It’s been over a week since we sent our last letter, and since then, our petition…

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນອາທິດ ທີ 21 ເມສາ 2019

“Clearly, consumers and the general public feel that harvesting and profiting from the creative work of others, particularly ethnic minority groups in developing countries, is wrong, and allowing it to go unchecked sets a dangerous precedent,” the letter from TAEC to Luigi Maramotti, Chairman of Max Mara, states.

“As the chairman of your privately-owned company, we are now reaching out to you directly. Please demonstrate ethical and moral leadership in the fashion and textile industry.”

“We ask that you pull this line from your stores, online shop, and resellers, issue a public statement committing to not plagiarise in the future, and lastly, donate the proceeds earned from the sales of these designs to an organisation of your choice that works to the protect the rights of ethnic artisans around the world.”

VS

VS

Efforts to raise awareness to the plight of the intellectual property of some of Laos most remote communities is being spearheaded by the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre of Luang Prabang.

The Petition started by TAEC and addressed to Max Mara Chairman Luigi Maramotti and Designer Director Laura Lusuardi states:

“Max Mara, a billion dollar Italian fashion house, plagiarised traditional designs of the Oma ethnic minority group from Laos.

“This is not the first time that a fashion brand has copied or appropriated designs of an ethnic group from developing countries, and past experience has shown that these companies are only likely to respond when faced with public pressure and negative press.

“Max Mara digitally duplicated and printed the designs onto fabric, reducing painstaking, traditional motifs to factory-produced patterns.

“The colors, composition, shapes, and even placement are identical to the original Oma designs. The company has not acknowledged the Oma in marketing, labeling, or display of the collection in its stores and online shop, nor has compensation been paid.

“The Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre is calling for Max Mara to (1) pull the clothing line from its stores and online, (2) publicly commit to not plagiarising designs again, and (3) donate 100% of the proceeds already earned from the sale of these garments to an organisation of its choice that advocates for the intellectual property rights of ethnic minorities. More information can be found on TAEC’s Facebook page.

“A largely agrarian community, the Oma live in the remote mountains northern Laos, northwestern Vietnam and southern China.

“Their exact population and number of villages is difficult to establish, as they are often grouped as part of the larger Akha ethnic group. However, it is estimated that in Laos there are fewer than 2,000 Oma across seven villages.

“Traditional clothing is still a vital part of the identity and pride of Oma people — handspun, indigo-dyed garments with vibrant red embroidery and applique is distinctive and unique to their group.

“In recent years, Oma women have begun to earn income through the sale of their distinctive crafts. In remote communities with few economic opportunities, these earnings are vital, and used towards improved nutrition, health, and education for their families.

“Founded in 1951 by Italian Achille Maramotti, Max Mara Fashion Group has grown into an international fashion powerhouse with over 2,200 stores in 105 countries and an online shop.

In 2017, Max Mara Fashion Group recorded global sales of €1.558 billion, across all brands. Unlike most couture houses which are publicly traded or held by multinational corporations, Max Mara Fashion Group is privately-held and helmed by Luigi Maramotti, CEO and a member of the original founding family.

“This is not an example of simple cultural appropriation, where designers utilize ‘ethnic-inspired’ elements, colors, materials, or styling, toeing the murky line between appreciation and appropriation.

“This is stealing the work of artisans who do not have the tools to fight it on their own,” states Tara Gujadhur, Co-Founder of the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre (TAEC), a social enterprise founded to celebrate and promote Laos’ ethnic cultural heritage and support rural artisans.

“TAEC’s small team based in Luang Prabang, Laos, is working to draw attention to Max Mara Fashion Group’s negligent behavior. Upon discovering the company’s plagiarism purely by chance on 2 April 2019, they sent repeated emails and messages to Max Mara’s headquarters, with no response.

“As a result, TAEC took to social media to amplify their message. The company finally responded on 10 April, but has not issued any apology or admitted their mistake, simply demanding the campaign cease, and then threatening potential legal action.

“A design is intellectual property, whether it’s sketched in a notebook by an illustrator, mocked up by a graphic designer on a computer, or embroidered on indigo-dyed cotton in a remote village in Laos.

“If it’s generally understood that using someone’s photography or written work without acknowledgment or permission is wrong, why would a handcrafted textile design be any different?” states Gujadhur.

“For this behavior to go unchecked is dangerous, as it sends the message that creative work that is traditional and shared by a community and culture in the developing world does not deserve the same kind of protections given to contemporary designs by individual ‘artists’ in the West. Companies can harvest motifs, materials, and ideas freely from communities that lack the educational, financial, and technological resources to have their rights recognized,” elaborates Gujadhur.

TAEC began working with the Oma in Nanam Village in 2010, when the organization was hired by a German development agency to survey their crafts and identify potential income-generating opportunities for the community. Since then, TAEC has helped Nanam to create more market-oriented products, such as pouches, cuffs, and wine bottle sleeves, generating much-needed cash for the women artisans and their families.

“The handicrafts are sold in TAEC’s museum shops in Luang Prabang, a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of Laos’ few cities that draws significant international tourism. Currently, TAEC works with over 30 communities across Laos, with fifty percent of the proceeds from their shops flowing directly to artisans.

TAEC has spoken to Khampheng Loma, the headman of Nanam Village, and not surprisingly, he was somewhat unclear about the issue. “The artisans we work with live in a very remote community, so their life experience is completely removed from issues of intellectual property rights. However, we will continue to discuss it with them, as we recognise this as an important, long-term process,” according to Thongkhoun Soutthivilay, TAEC’s Co-Director, who works closely with the Oma women on handicraft production.

“Each motif has a special meaning,” Loma shared. “Our tradition of embroidery makes us who we are. In our culture, you have to know how to embroider to be able to call yourself Oma.”