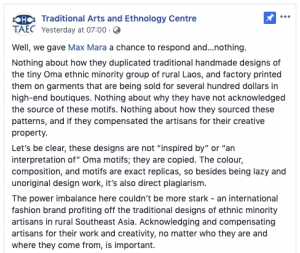

The Laotian Times looks at the plagiarism accusations lodged against fashion chain Max Mara by the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre. In doing so, we also welcome the chance to publish Max Mara’s response to these claims as soon as they become available.

Alleged plagiarism of traditional designs of ethnic minority groups has hit the headlines in Laos with Italian born private fashion chain being accused of pilfering the property of the Oma people, an ethnic group who reside in the mountainous north and north-east of South East Asia’s multiethnic Laos.

No mention of origin. Products promoted on Max Mara Weekend Zagreb Instagram. #MaxOma Direct link:https://www.instagram.com/p/BvqktKiHM6A/(update: Max Mara has taken down this social media post!)

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

Weekend MaxMara Zagreb

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

Social media shares have hit the thousands for the underdog story of the year as the diminutive cultural community of a small number of villages goes into bat against global fashion giant Max Mara after the discovery of the alleged design theft in Croatia.

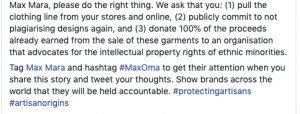

The campaign calls for Max Mara to (1) pull the clothing line from its stores and online, (2) publicly commit to not plagiarising designs again, and (3) donate 100% of the proceeds already earned from the sale of these garments to an organisation that advocates for the intellectual property rights of ethnic minorities.

Side by side comparison. #MaxOma

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

Multi-million dollar fashion brand Max Mara is exploiting cultural designs and heritage of the Oma, an isolated ethnic minority group in northern Laos, without any acknowledgment or compensation, Luang Prabang’s Traditional Arts & Ethnology Centre alleges.

No mention of origin of the "ethnic print" or the Oma on their website. #MaxOma

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

“Our grandparents passed down these traditions to our parents, and our parents to us. We are the Oma people, and we preserve our culture by making and wearing our traditional clothes. We need them especially for funeral rites, out of respect to our ancestors.” – Khampheng Loma, Head of Nanam Village

Campaigning alongside Laos’ Oma people is the Traditional Arts & Ethnology Centre in UNESCO World Heritage Listed Luang Prabang.

In fact, it was the discovery of the alleged examples of appropriation by the centre’s staff in far-away Croatia that has led to the accusations against the fashion giant.Lauren Ellis, former employee of Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre and current museums curator based in Melbourne.

Side by side comparison. #MaxOma

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

Her reaction when she discovered the Max Mara collection in one of the brand’s stores in Zagreb, Croatia?

“I had to do a double take. It was only because I had worked in Laos that I immediately recognized the designs as Oma. They had copied the patterns exactly. I couldn’t believe that this major brand would sell such blatantly stolen designs.”

Now, together the Oma and the TAEC are highlighting appropriation of the owners’ intellectual property following alleged Infringements by the Italian-founded fashion chain Max Mara.

“Working with embroidery and applique is very challenging. Each motif is difficult and time-consuming to make. But, this is our tradition. Now, we can make products to sell to help support our families.” – Khampheng Loma, Head of Nanam Village

Side by side comparison. #MaxOma

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

“The handmade textiles of the Oma are incredibly detailed, taking a huge amount of time, skill, and patience. To see them reduced to a printed pattern on a mass-produced garment is heartbreaking.” – Tara Gujadhur, TAEC Co-Director

Side by side comparison. #MaxOma

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

“The issue here is not the integration of Oma motifs in a more globalized world through the collection of Max Mara,” Dr. Lissoir said.

Cultures are fluid. Communities and their traditions and handicrafts are in constant change. They adapt themselves and get inspired by other cultures. Always have, always will.

However, Max Mara didn’t get inspired by Oma motifs and reinterpret them. They simply scanned a handmade piece and printed it on clothes without even mentioning the existence of Oma community.

This is not cultural appreciation. This is not creative interpretation. This is plagiarism.”

TAEC’s full statement reads:

“ITALIAN FASHION BRAND MAX MARA PLAGIARISES DESIGNS OF ETHNIC MINORITY GROUP IN LAOS”

“Multi-million dollar fashion brand Max Mara is exploiting cultural designs and heritage of the Oma, an isolated ethnic minority group in northern Laos, without any acknowledgement or compensation, Luang Prabang’s Traditional Arts & Ethnology Centre alleges.

Max Mara Fashion Group, a multi-billion dollar Italian couture fashion house plagiarised traditional designs of the Oma ethnic minority group in their Spring/Summer 2019 collection.

The patterns appeared in dresses, skirts and blouses presented in the collection’s “Max Mara Weekend” resort line.

The Oma, a small ethnic community living in the hills of Phongsaly Province in northern Laos, embroider, stitch, and appliqué these colorful designs onto their traditional clothing, including head scarves, jackets, and leg wraps.

Max Mara digitally duplicated and printed the designs onto fabric, reducing painstaking, traditional motifs to factory-produced patterns.

The colours, composition, shapes, and even placement, are identical to the original Oma designs. Max Mara’s design and marketing team has not acknowledged or compensated the Oma in marketing, labeling, or display of the collection in their stores and online shop, nor have they responded to urgent enquiries on the issue.

A largely agrarian community, the Oma live in the remote mountains northern Laos, northwestern Vietnam and southern China. Their exact population and number of villages is difficult to establish, as they are often grouped as part of the larger Akha ethnic group.

However, it is estimated that in Laos there are fewer than 2,000 Oma across seven villages.

Traditional clothing is still a vital part of the identity and pride of Oma people — handspun, indigo-dyed garments with vibrant red embroidery and applique is distinctive and unique to their group.

In recent years, Oma women have begun to earn income through the sale of their distinctive crafts. In remote communities with few economic opportunities, these earnings are vital, and used towards improved nutrition, health, and education for their families.

Founded in 1951 by Italian Achille Maramotti, Max Mara Fashion Group has grown into an international fashion powerhouse with over 2,200 stores in 105 countries and an online shop.

In 2017, Max Mara Fashion Group recorded global sales of €1.558 million, across all brands.

Unlike most couture houses which are publicly traded or held by multinational corporations, Max Mara Fashion Group is privately-held and helmed by Luigi Maramotti, CEO and a member of the original founding family.

Co-Founder of the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre (TAEC), a social enterprise founded to celebrate and promote Laos’ ethnic cultural heritage and support rural artisans, is Tara Gujadhur.

“This is not an example of simple cultural appropriation, where designers utilize ‘ethnic-inspired’ elements, colors, materials, or styling, toeing the murky line between appreciation and appropriation,” Gujadhur said.

“This is stealing the work of artisans who do not have the tools to fight it on their own,”

TAEC’s small team based in Luang Prabang, Laos, is working to draw attention to Max Mara Fashion Group’s negligent behavior.

Upon discovering the company’s plagiarism purely by chance, they sent repeated emails and messages to Max Mara’s headquarters, with no response.

As a result, TAEC is now taking to social media to amplify their message and enlist the public’s support.

A call for action is being shared from TAEC’s Facebook and Instagram page (@taeclaos), where photo comparisons of the products can be found, as well.

“A design is intellectual property, whether it’s sketched in a notebook by an illustrator, mocked up by a graphic designer on a computer, or embroidered on indigo-dyed cotton in a remote village in Laos. If it’s generally understood that using someone’s photography or written work without acknowledgment or permission is wrong, why would a handcrafted textile design be any different?,” Gujadhur said.

“Over the past three decades, protecting the intellectual property rights of the third world and indigenous peoples has become recognized as crucial, although how this should be done is much more debatable. We are looking at ways to assist the communities we work with to tackle this issue.”

“For this behavior to go unchecked is dangerous, as it sends the message that creative work that is traditional and shared by a community and culture in the developing world does not deserve the same kind of protections given to contemporary designs by individual ‘artists’ in the West.

“Companies can harvest motifs, materials, and ideas freely from communities that lack the educational, financial, and technological resources to have their rights recognized.”

TAEC began working with the Oma in Nanam Village in 2010 when the organization was hired by a German development agency to survey their crafts and identify potential income-generating opportunities for the community.

Since then, TAEC has helped Nanam to create more market-oriented products, such as pouches, cuffs, and wine bottle sleeves, generating much-needed cash for the women artisans and their families.

The handicrafts are sold in TAEC’s museum shops in Luang Prabang, a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of Laos’ few cities that draws significant international tourism.

Currently, TAEC works with over 30 communities across Laos, with fifty percent of the proceeds from their shops flowing directly to artisans.

TAEC has spoken to Khampheng Loma, the headman of Nanam Village, and not surprisingly, he was somewhat unclear about the issue.

“The artisans we work with live in a very remote community, so their life experience is completely removed from issues of intellectual property rights.

However, we will continue to discuss it with them, as we recognize this as an important, long-term process,” according to Thongkhoun Soutthivilay, TAEC’s Co-Director, who works closely with the Oma women on handicraft production.

“Each motif has a special meaning,” Loma said.

“Our tradition of embroidery makes us who we are. In our culture, you have to know how to embroider to be able to call yourself Oma.”

TAEC’s campaign to draw attention to this issue is now live, using Facebook, Instagram, and influencers across platforms to call out Max Mara’s plagiarism.

The campaign calls for Max Mara to (1) pull the clothing line from its stores and online, (2) publicly commit to not plagiarising designs again, and (3) donate 100% of the proceeds already earned from the sale of these garments to an organisation that advocates for the intellectual property rights of ethnic minorities.

The Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre (TAEC) is a local social enterprise founded in 2006 to promote the appreciation and transmission of Laos’ ethnic cultural heritage and livelihoods based on traditional skills.

The Centre’s primary activities are two-fold: a museum, and fair-trade handicrafts shops directly linked with artisan communities. The Centre’s work includes school outreach activities, craft workshops, lectures, research, and a non-profit foundation.

What did Max Mara do?

Max Mara used traditional designs of the Oma ethnic minority group in their Spring/Summer 2019 collection for the “Max Mara Weekend” clothing line, without acknowledgment, and likely without permission or compensation. Oma women embroider, stitch, and appliqué these designs onto their traditional clothing, including head scarves, jackets, and leg wraps. Max Mara had these designs digitally duplicated and printed onto fabric, reducing painstaking, traditional motifs to factory-produced patterns. The colors, composition, shapes, and even placement are identical to the Oma designs.

Who are the Oma?

The Oma are a small ethnic group living in mainland Southeast Asia. They speak a language belonging to the Sino-Tibetan ethnolinguistic family, like the Akha – a community more numerous and widely recognized by the general public. While Oma are often described as a sub-group of Akha ethnic group (and called “Akha Oma”), many consider themselves a distinct community. This association with the Akha makes the exact population and number of villages of the Oma difficult to pin down. However, it is estimated that there are fewer than 2,000 Oma in Laos, inhabiting seven villages in Phongsaly province. Small Oma communities may also exist in neighboring southern China, northwest Vietnam, and Myanmar.

Can copying a design be considered “plagiarism?”

Absolutely. A design is intellectual property. Whether it’s sketched in a notebook by an illustrator, mocked up by a graphic designer on a computer, or embroidered on indigo-dyed cotton in a remote village in Laos. If it is generally understood that using someone’s photography or written work without acknowledgment or permission is wrong, why would a handcrafted textile design be any different? Over the past three decades, protecting the intellectual property (IP) rights of third-world and indigenous peoples has become recognized as essential, though how it should be done is much more debatable.

TAEC Co-Director, Tara, working with the Oma artisans in 2017 to understand the time involved in creating their clothing.Photo credit: Radium Tam

Posted by Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre on ວັນຈັນ ທີ 8 ເມສາ 2019

If the designs have no patent, how can Max Mara be held accountable?

Public opinion. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for traditional knowledge, artwork, design, and ideas to be co-opted by multinational corporations who have the power and financial clout to either ignore IP claims or drag them out in court. However, we have seen that a public outcry, negative press, and boycotting of brands can pressure companies to admit wrongdoing and improve their practices.

What should Max Mara have done if they wanted to feature the Oma’s designs?

They had many options. They could have approached the Oma community or artisans directly, and ordered their handmade work for a fair price to incorporate into their clothing, generating income for the community. There are organizations, like Nest, that work with brands to help link them to artisan groups and social enterprises in developing countries to collaborate. These partnerships can result in wonderfully creative products that also generate great visibility and earnings for both the brand and the communities. At the very least, Max Mara should have attributed the designs to the Oma (avoiding the generic “ethnic” term) and committed a certain percentage of profit to go towards education, rural development, or advocacy work with Oma communities.

How has the Oma community reacted to this issue?

The Oma artisans TAEC works with live in a very remote community, so their life experience is completely removed from issues of intellectual property rights. However, we will continue to discuss it with them, as we recognize this as an important, long-term process.

If they don’t understand the issue, why does it matter?

Plagiarism is wrong, whether the plagiarised feel wronged or not. Letting this kind of corporate behavior go unchecked is dangerous, as it sends the message that creative work that is traditional and shared by a community and culture in the developing world does not deserve the same kind of protections given to contemporary designs by individual “artists” in the West. Companies can harvest motifs, materials, and ideas freely from communities that lack the educational, financial, and technological resources to have their rights recognized.

How did TAEC get involved?

TAEC has worked with the Oma since 2010 when we were hired to survey their crafts and identify potential income-generating opportunities for their artisans. Most recently, we have worked with them on documenting their traditional music and new year’s celebrations. Nanam Village is an approximately 9-hour drive from Luang Prabang, part of it unpaved, and is by far the most remote village (of 30 across Laos) that TAEC works with.

On Tuesday, 2 April 2019, a friend and former colleague was in Zagreb, Croatia, and saw the designs through a Max Mara shop window. She immediately shared pictures with us. Amazed, we initially thought it might be actual handcrafted work from the Oma that was incorporated into the clothing. Upon further examination, it became clear that not only were the Oma not credited in the name of the garment, on tags, or online, but the motifs were simply digitally reproduced and mass-printed. TAEC immediately reached out to Max Mara’s headquarters through various e-mail addresses and social media channels. After a week with no response, TAEC feels it’s important to make this issue public.

What should Max Mara do now to right this?

Max Mara should: (1) pull the clothing line from its stores and online, (2) publicly commit to not plagiarising designs again, and (3) donate 100% of the proceeds already earned from the sale of these garments to an organization that advocates for the intellectual property rights of ethnic minorities.”